|

| So-called crypta Neapolitana of Seneca |

Traveling from the Roman resort of Baiae to Naples one day nearly 2000 years ago, the Stoic philosopher Seneca decided to take the land route instead of the short but choppy sea voyage. Part of the road took a shortcut through a mountain by means of the famous Naples Tunnel. But the Crypta Neapolitana turned out to be almost worse than a sea voyage, a virtual ‘visit to death’. In one of his famous Letters to Lucilius, Seneca describes his harrowing journey.

|

| bronze portrait thought by some to depict Seneca |

Emerging from the gloom into daylight restored Seneca to his usual good spirits, but thinking about the claustrophobic darkness of the tunnel afterwards prompted him to write about the nature of death and the immortality of the soul.

|

| Mergellina station seen from Tomb of Virgil |

|

| Hand-made tile plaque about myrtle at Virgil's Tomb |

Another plaque tells about Virgil and you can see a modern bust of him in a niche, done in 1930 on the 2000th anniversary of his birth. Although the poet was born in Mantua and studied in Rome, he called Naples his home.

The plaque reads:

|

| A modern bust of the ancient poet Virgil |

Mantua bore me, the Calabrians snatched me away, now Naples holds me. I sang of pastures, countrysides, leaders...

The steep hill is formed of honey-coloured tufa cloaked in ivy and dripping with vines. Like honeycomb, the soft rock is perfect for tombs, niches and tunnels, which the Neapolitans call galleria. The biggest of these tunnels is the dramatic Crypta Neapolitana – Seneca’s tunnel. Next to it is one contender for Virgil’s tomb, a cave carved into the hill with a bust of Virgil in a niche nearby. Nearby is another tomb, that of Giacomo Leopardi (1798-1837) a hunchback poet who was a great worshipper of Virgil. Sometimes this area is called the Hill of the Poets.

|

| Medieval fresco of Santa Maria dell’Idria above the tunnel |

Climbing the brick stairs with the aid of a sturdy wooden handrail we found a small Roman aqueduct that ran above Seneca’s tunnel. From up here you can get a closer look at a niche with a faded fresco of Madonna and Child. Mounting more stairs takes you to a beehive-shaped tomb that also might be Virgil’s. This atmospheric freestanding cylindrical tomb is of the columbarium type, with niches for ash-filled urns. There is a convenient tripod where you can burn fragrant bay leaves in memory of the great poet. The view from up here is breathtaking; you can see right across the bay to Vesuvius.

|

| Caroline Lawrence in Virgil's tomb |

Virgil the Magician also placed a magic hen’s egg somewhere in the eponymous Castel dell’Ovo. As long as the egg remains, goes the legend, the castle will stand strong.

|

| painting of the Naples Tunnel by Gaspar Vanvitelli c 1700 |

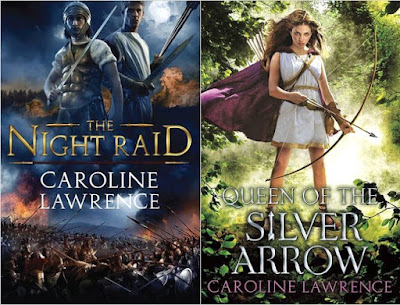

My two retellings of stories from Virgil’s Aeneid are The Night Raid, about Nisus and Euryalus from book 9, and Queen of the Silver Arrow, about Camilla from books 7 and 11. The reading level is easy but the content is dark.

A version of this post was originally published on the Wonders and Marvels blog.